Central Bark Episode 11

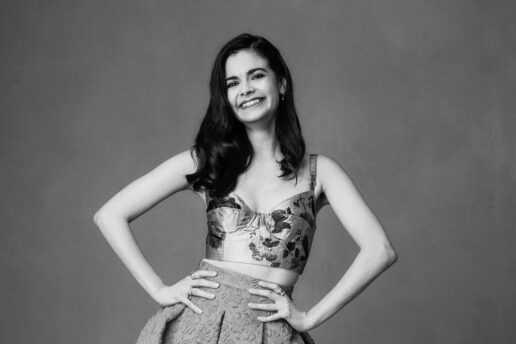

Melba Veléz-Ortiz and Chad

In this episode, Theresa is joined by GDB client and Alumni Board member, Melba Vélez-Ortiz. Melba talks about growing up in Puerto Rico, her passion for her career as a professor, and the transformative process of overcoming her fear of dogs and learning to communicate in new ways.

Greetings everyone. And welcome to this very special episode of Central Bark. Today, I am joined by Melba Velez Ortiz, and she is many, many things. She is a professor, she's an advocate, she's a GDB alumni, and most importantly, she's awesome. So welcome Melba.

Melba Veléz-Ortiz: Hi. Muchas gracias. Hola. Hello. Indeed, it is my pleasure to be here.

Melba: I know my name is a mouthful, but it is very important that I was born and raised in Puerto Rico, in the Caribbean. And there, we keep our mother's last name throughout our lives. So Velez is my paternal last name, but Ortiz is my maternal last name. And especially now that unfortunately my mom passed away two years ago, it has become ever more important to say her name. I feel like every time some people say her name in relation to mine, she smiles from heaven. So thank you so much for including it, it means so, so much.

Theresa: I love that, moms are very, very special, that is for sure. And the more we can keep them around us, the better. Now we might not have said that when we were 13, but after 20, it's pretty awesome.

Melba: Absolutely.

Theresa: Melba, you have quite a lot going on. I want to know a little bit about your background. I know you grew up in Puerto Rico and tell me a little bit about what that was like and moving to the US and all the amazing stuff you do.

Melba: It's wonderful. And it is amazing how these days people move around a lot, but there's always a place that we think of as home. And yes, I've been out of that tiny little island, which I'm not sure if our listeners know, but it's only 100 miles by 35, that's the whole thing.

Theresa: Wow.

Melba: Basically this is why they don't even bother drawing us on a map. You always see a little period with a name on it and that's why. But growing in that tiny little island was magical, it really was. I was a very inquisitive child. I wasn't able to involve myself in sports and I had tremendous trouble learning how to drive. I had in fact, not one, not two, but three collisions just trying to get my permit. And at the time I had not been diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa. So that little girl in the Caribbean grew up thinking, "Well, my goodness," I tried to play volleyball and the ball would land right in front of me and I would not move. None of that made sense until I got my diagnosis and then I, "Oh, that's why." But we don't have the privilege of seeing through anybody else's eyes, so I did not suspect that there was something wrong with my vision. I figured, "Well, I'm bad at sports or I cannot drive, I guess I'll just walk."

Theresa: You need a bus pass, yeah.

Melba: Get a bus pass. So I did not kind of grow up having conscious experience of a disabled person, but rather being puzzled by all these things that didn't make sense. And it was only when I moved to the US to attend college, that just by pure coincidence, I was going to get one of those one hour prescription glasses. I had lost mine, and I went quick to the place that was one hour. And while I waited for my new prescription, I remember the staff person said, "Well, we have a brand new test that's only $5." And at the time of course I was a poor college student, but even I could afford $5, so I was like, "All right. Well, if it's just $5."

It was actually an examination of my retina. And once the doctor came back, I immediately sensed something was really wrong. That's how I learned about this condition, which is a genetic, it's degenerative. At the moment, there's a bit of excitement in looking at a few treatments, but so far officially, there's still no cure or treatment, officially. And so it was to a 22 year old, being told, "Well, the thing is, you're going to lose your vision more than likely completely, but we don't know when, so good luck." Yeah, it's disheartening. But it kind of set me on a path that has taken me where I am today. And well, overall it's been a joy ride, honestly.

Theresa: That's awesome. So tell me a little bit about that path. So you found out you're losing your vision. You're just about to start college. So tell me how all that worked out. And you didn't just go to college, you went and got your PhD.

Melba: Yes.

Theresa: You went for a long time. Tell me a little bit about how that worked for you and just sort of accommodations that you had to make and all that stuff.

Melba: Happy to. For one thing, this is something that I get to use now, this knowledge I get to use on a regular basis, because when I was an undergrad, I went through a pretty serious denial phase for many reasons. First of all, when you're given an incurable diagnosis like that, you're going to resist it to some extent. And because the degeneration of the retina occurs over time, you do fool yourself for a long time. In addition to that, my parents also had a very, very difficult time with the diagnosis. And for your listeners, I don't know if they can relate to this, but my parents wanted the best for me. And neither one of them could conceive that they had given this to me, you see.

So, that this is what was going on with them. Did I do this to her? Is it my fault? Is it in my genes? So they went through their own denial period, took me to many, many doctors. All of them came back with, "Sir, ma'am, she has a textbook case of this thing. Yeah, it is what it is." So it took them a long time. Now here's and I struggled with this. In fact, I never said I couldn't read any of the boards because in addition to the severe tunnel vision that retinitis pigmentosa produces in one, I also was not able to read the board. My central vision wasn't good enough for me to read a blackboard, but I never told a soul. I never told a soul anything. For me, there's a bit of a different dynamic, Theresa, because here I am, a Hispanic woman, a young woman, and I'm going to the school in the US.

And I'm learning about how Hispanics are seen, and Latinos are seen. All of these politics are foreign to me, I did not grow up here. So the fact that I had to disclose that in addition to having this big Spanish accent and being 4 feet, 8 inches, and being from somewhere else, now I have to tell people I'm blind too. So even in my teaching, I remember being a TA and not saying a word and students would have... Because remember, I have severe tunnel vision and students would raise their hands in the corners of the classroom, and I would not call on them. And for the longest time, I was given the impression that I was ignoring people, so that is what prompt me to finally start disclosing in the classroom.

And actually by the time I got to University of Illinois to finish the story and I get to do my PhD, Illinois had what is, in my opinion, the best disability services office I've ever interacted with, in all my years of schooling. They have disability specific counselors and my guy was Brian McMurray and he took me through this kind of journey of acceptance because this is something I really want to share with your listeners. Just because a person gets a diagnosis, especially a young person, doesn't mean A, that they A, accept it. Two, understand it. Three, know what to do. And the current model that we have, particularly in institutions of higher education to provide services for students, depends on them coming to us and saying, "Well, this is what I need," but I had no idea what I needed.

So it was having the experience of having Brian kind of lead me through it that made me become mobility trained. And I became a cane user at that time. Now you fast forward some years later, and I'm seeing a therapist whose father got a dog from Guide Dogs for the Blind in San Rafael and that leads to the next chapter. But yes, that's how I came upon Guide Dogs in the state of Michigan of all places.

Theresa: Of all places, isn't it funny that network of people that are all kind of out there helping each other along, kind of mentoring you through some of these difficult things. And then now you're kind of in the seat doing that with other people.

Melba: Absolutely, yes.

Theresa: Tell me a little bit about, because I think sometimes people will hear that they're losing vision and be like, "Oh, I'm definitely going to get a dog," and they don't even realize they need to learn the cane first or whatever. It sounds like you learned the cane first, which was great and I think I've heard that you were a little bit tentative about wanting to explore the guide dog lifestyle.

Melba: Accurate, completely accurate. First of all, we have to, in my case, we expand our universe a little bit. And we think of this in global terms and where I'm from, dogs are not always regarded with the same care that they are in the United States. In fact, there is a sizeable and growing problem of stray dogs back home. And neither one of my parents came from a particularly distinguished background, so they lived in this sort of poor neighborhoods where these dogs existed. Well at the age of nine, my mom was bitten by one of these dogs. And guess what? When it came time to raise myself and my brother, she spent lots of time telling us to beware of dogs, to be scared of dogs, to never approach a dog.

And so she inculcated that fear in us. I had no experience, no nothing, but a little bit of terror. And so I kind of forced myself to go through the program. Part of the reason for that is my therapist, who was the one whose dad had a dog from Guide Dogs, told me this one thing. And I wonder if anybody else can resonate with this. But she said, "I know that you are using your cane and you feel like you're doing okay with your cane. But imagine having the ability to take a walk," she says, "Just enjoy it." That's what she said. My world exploded. I was like, "Enjoy it. How?" That was unheard of for me. And it was the goal of being able to one day walk with my dog and being able to enjoy my work that kind of led me through overcome and deal with my fear and finally get the amazing Chad.

Theresa: That is fantastic. And I think it's interesting when you say that, because I know being somebody like for me anyway, walking with a cane was great and I could get around okay, but I was always really having to tune in a little more, I think, than like you said with a dog, just kind of going for a fun walk. Yeah, no I love that.

Melba: It is and you get to feel the breeze and the elements. It's a completely different experience. And I suspect, especially for women, if you're walking alone particularly.

Theresa: So tell me what it was like when you first took that first sort of freedom walk, I guess with Mr. Chad, I want to know all about that.

Melba: Amazing. Now you have to also think about the fact that as far as my training, all my degrees are in communication. So I am somebody who has a passion for the study of how humans talk to one another well, and I have been such a big fan of this topic, that I have gotten all the degrees you could possibly get in that.

Theresa: That surprises me Melba, I'm very surprised that you studied communication because you seem to be so shy.

Melba: Who would've thought, somebody has introverted as myself. Well, Chad provided me actually an amazing challenge because I know a lot about how people can relate through conversation, but I had no idea how two different species possibly come together and work to achieve the same goals. So intellectually, my brain is already going 100 miles an hour. And personally, I'm experiencing yes, my freedom walks. And I must say that, as someone who has benefited from the teaching of so many, Chad figures among maybe the top five teachers I've ever had.

Theresa: Is that right? Tell me more about that. What have you learned from Mr. Chad?

Melba: He's amazing. Think about this. So I am not only someone who is completely losing her vision, but I'm also someone who primarily deals in the world of ideas. I get to write and I get to teach for a living, so my job doesn't really require, shall we say, a lot of physicality. Well, here comes my partner, Chad, who is very physical and for whom words matter not so much, but it's all action. So now the emphasis and the attention I'm putting on things and my focus has shifted from looking for words, to looking for actions. And for someone like me who is so often sort of lost in ideas, I have a partner who, and this is what maybe my favorite lesson Chad has ever taught me. We were outside and I was kind of cleaning the yard and such and Chad, all of a sudden decided that he was just going to go in the grass and just lay back and enjoy himself.

And upon grazing at him a few times, I felt like, "You know what, maybe there's something to what he is doing. I'm going to go try it out." So here goes the professor and lays next to Chad and had the amazing lesson of a lifetime, just learning how to be still, just learning how to quiet this mind that's going often 100 miles an hour and just smell the grass and feel the breeze. And he did that with such gentleness and such patience and it's something, Chad keeps me grounded. Chad gives me engaged. Chad keeps me sane. He has become such an important part of my life and it's always with love and support that he teaches me these things, it's never with bad intention or hesitantly, he gives and he gives generously. And I have everybody else call him Professor Chad. Why?

Theresa: Professor Chad.

Melba: Because he teaches unconditional love and service.

Theresa: Yeah, that is so powerful to me because you're right. It's just living in the moment, just feeling the grass, listening to the birds, whatever it is, but that's a beautiful, beautiful lesson. And I think, it has to be taught over and over again, at least I think in my life, to remember to stop.

Melba: I agree and people who have permanent disabilities, we also spend quite a amount of time planning ahead, we don't have the luxury oftentimes to be completely spontaneous, like, "Oh, I'm just going to get in my car," and we don't have that. So Chad has brought a little bit of that spontaneity and that being in the moment. I'm telling you, he has been absolutely crucial to my, I would say, my spiritual wellbeing and my mental wellbeing, there's no question.

Theresa: Oh, amazing. Just amazing. So I know in your sort of field and things that you've worked on, I know you're really, you said about communication and inclusion and do you see any sort of synergies between the field that you've gotten into? And I think probably some of it having to do with your experience as a person with visual impairment and sort of Guide Dogs for the Blind and our vision of a world of inclusion.

Melba: Yes. Oh 100%. And here, I'm going to get a little bit nerdy, but not too, too much. I'm keeping my feet on the ground. But I recently wrote a piece for a listening journal called, Blindness as Inferior. And what I mean by all of that fancy wording is, there's a way in which historically, I want to take you back to ancient times, for example. People have talked about blindness as either gift or curse. So it's rather something that maybe God punished you with for something you did or its some kind of gift that makes you special and kind of divine in some ways. But to be blind in the 21st century, in the United States, means you are just like everybody else. This is not a gift and it is not a curse. It's a different way to be.

And particularly, when we look at the way in which blindness has been depicted as a curse has been really, really detrimental, particularly because blindness, if you think about it, how people use it in conversation every day, it has some derogatory association with it. To be blind is to be what, ignorant to be stupid, to have missed something important?

So here I am, Theresa, a walking contradiction because I am the blind knower. I know things. I too, you see, I'm a repository of knowledge and science and everything else, but I am losing more and more vision every day. So it is crucial that students in my community, looks at a blind person and I'm using the word look very intentionally, looks as a blind person, as someone with expertise, not a fool, not a silly person, but someone who knows and whose knowledge is to be valued. So every day, Chad and I are on a mission to spread that message. Because every time people talk about blindness as something that is a curse or something that is just describing a person who's foolish and doesn't know anything, that impression keeps lingering. So Chad and I are here to fight it, cape and all.

Theresa: I love it. It's so true. And I think, you personify that sort of positive person, who has a lot of knowledge to give, in fact, I'm thinking, how do I sign up for one of your classes, Melva? [inaudible 00:20:19]. I want to go back to school.

Melba: That's the most exciting thing because the other thing I teach is how you can turn something that maybe other people think is a weakness into a strength. So the best thing I'm doing this year, and I just finished is teaching listening. I took it upon myself to learn listening as a skill set, as a professional skill set. And now I get to teach that to my students. And let's be frank, who better than teach you how to listen, than a blind person, when my life depends on it. So I get to do that now. And that's another contribution I make, because if you think about the college experience, most people have to take the dreaded speech class, but who here remembers taking a listening course, I'll wait.

Theresa: Yeah.

Melba: Exactly. So see, had it not been for this experience, I wouldn't have even an additional area of expertise now. And that's what I want my students to learn, that no matter what life throws at you, you can adapt. You can adapt and you can keep going, no matter what.

Theresa: Wow. So it sounds like, Guide Dogs for the Blind, sort of your personal philosophy of inclusion and really seeing the connections I think between people and the community, it all just kind of all flows so well together. And I'm wondering, because you have become part of our alumni association, board of directors at Guide Dogs for the Blind and we love having you and your amazing perspectives on things. So tell me a little bit about why you decided you wanted to get even more involved in the GDB community.

Melba: I had been waiting for this opportunity ever since I graduated back in 2015, I've been waiting for this because take it from someone who has done, you cannot get any nerdier than I. No one, if there's a bookworm, you're looking at it or you're hearing her, either way.

Theresa: You're a bookworm, but you're a bookworm with a lot of razzle dazzle Melba, I'll you that.

Melba: Well, some of us do come with some extras. But someone who is a [inaudible 00:22:41] is here to tell you, GDB or Guide Dogs for the Blind, has been the most significant educational experience of my life. I'm going to say it one more time. Guide Dogs for the Blind has been the most valuable and meaningful and helpful educational experience of my life. Nothing else I've ever done, has pushed me to believe in myself and to get into the minds of amazing resilient people like guide dogs. It's not just what you learn about dogs and what you get from working with the dogs. It's about the people who are there, from the instructors to the staff, to my peers.

This is a fountain of knowledge and inspiration that is simply not available any place else. And I had been waiting to give back. And for those of us who have tried more than once to get on the board, I'm here to say, persistence pays off, because this was not my first time applying to be on that board. But when you believe in something and you really want to be a part of it, you keep trying year, after year, after year, after year, until you make it in. And it's been so worth it to just share ideas and work elbow to elbow with so many brilliant advocates. GDB is the place where I, the professor, turn into a lifelong learner and that's why I love it so much.

Theresa: Wow. Well, we love having you on board and timing is everything Melba.

Melba: Thank you. I'll never have enough to repay Guide Dogs for what they've done for me, but I'm not going to stop trying.

Theresa: Okay. Well, we'll take that. It has been an absolute pleasure having you on. I always feel like when I'm with you, that I've just a couple of speedometers down from [inaudible 00:24:46] you're so on top of everything all the time and so lovely and lively, thank you so much. Thank you for being part of Central Bark. Thank you for being part of Guide Dogs for the Blind community. I hope you'll come back and join us again sometime.

Melba: The feeling is mutual and I would love nothing more, muchas gracias.

Theresa: For more information about Guide Dogs for the Blind, please visit guidedogs.com.

Related Episodes